D. B. Cooper

| D. B. Cooper | |

|---|---|

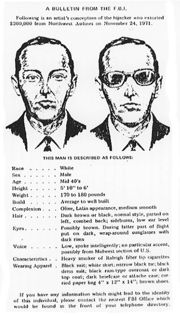

A 1972 F.B.I. composite drawing of D. B. Cooper |

|

| Other names | Dan Cooper |

| Occupation | Unknown |

| Known for | Hijacking a Boeing 727 on November 24, 1971, and parachuting out of the plane in flight |

D. B. Cooper is the name attributed to a man who hijacked a Boeing 727 aircraft in the United States on 24 November 1971, received US $ 200,000[1] in ransom, and parachuted from the plane. The name he used to board the plane was Dan Cooper, but through a later press miscommunication, he became known as "D. B. Cooper". Despite hundreds of leads through the years, no conclusive evidence has ever surfaced regarding Cooper's true identity or whereabouts, and the bulk of the money has never been recovered. Several theories offer competing explanations of what happened after his famed jump, but the F.B.I. believe he did not survive.[2]

The nature of Cooper's escape and the uncertainty of his fate continue to intrigue people. The Cooper case (code-named "Norjak" by the F.B.I.)[3] is the only unsolved U.S. aircraft hijacking,[4] and one of the few such cases anywhere in the world, along with Malaysia Airlines Flight 653.

The Cooper case has baffled government and private investigators for decades, with countless leads turning into dead ends. As late as March 2008, the F.B.I. thought it might have had a breakthrough when children unearthed a parachute within the bounds of Cooper's probable jump site near the town of Amboy, Washington.[5] Experts later determined that it did not belong to the hijacker.

Despite the case's enduring lack of evidence, a few significant clues have arisen. In late 1978 a placard containing instructions on how to lower the aft stairs of a 727, later confirmed to be from the rear stairway of the plane from which Cooper jumped, was found just a few flying minutes north of Cooper's projected drop zone. In February 1980 on the banks of the Columbia River, eight-year-old Brian Ingram found $5,880 in decaying $20 bills, which proved to be part of the original ransom.[6]

In October 2007, the F.B.I. claimed that it had obtained a partial DNA profile of Cooper from the tie he left on the hijacked plane.[7] On December 31, 2007, the F.B.I. revived the case by publishing never-before-seen composite sketches and fact sheets online in an attempt to trigger memories that could possibly identify Cooper. In a press release, the F.B.I. reiterated that it does not believe Cooper survived the jump, but expressed an interest in ascertaining his identity.[7][8]

Contents |

Hijacking

On Wednesday, November 24, 1971, the day before Thanksgiving in the United States, a man traveling under the name Dan Cooper boarded a Boeing 727-100, Northwest Orient (subsequently Northwest Airlines, now part of Delta Air Lines) Flight 305 (FAA Reg. N467US), flying from Portland International Airport (PDX) in Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington.[9] Cooper was described as being in his mid-forties, and between 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) and 6 feet (1.83 m) tall. He wore a black raincoat, loafers, a dark suit, a neatly pressed white collared shirt, a black necktie, black sunglasses and a mother of pearl tie pin.[10] Cooper sat in the back of the plane in seat 18C. After the jet had taken off from Portland, he handed a note to a young flight attendant named Florence Schaffner,[11] who was seated in a jumpseat attached to the aft stair door, situated directly behind and to the left of Cooper's seat. She thought he was giving her his phone number, so she slipped it, unopened, into her pocket.[12] Cooper leaned closer and said, "Miss, you'd better look at that note. I have a bomb."[13] In the envelope was a note that reportedly read: "I have a bomb in my briefcase. I will use it if necessary. I want you to sit next to me. You are being hijacked."[14]

The note also provided demands for $200,000, in unmarked bills, and two sets of parachutes—two main back chutes and two emergency chest chutes.[15] The note carried instructions ordering the items to be delivered to the plane when it landed at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport; if the demands were not met, he would blow up the plane.[16] When the flight attendant informed the cockpit about Cooper and the note, the pilot, William Scott, contacted Seattle-Tacoma air traffic control, who contacted Seattle police and the F.B.I.. The F.B.I. contacted Northwest Airlines president Donald Nyrop, who instructed Scott to cooperate with the hijacker.[15] Scott instructed Schaffner to go back and sit next to Cooper, and ascertain if the bomb was in fact real. Sensing this, Cooper opened his briefcase momentarily, long enough for Schaffner to see red cylinders, a large battery, and wires, convincing her the bomb was real.[17] He instructed her to tell the pilot not to land until the money and parachutes Cooper had requested were ready at Seattle-Tacoma. She went back to the cockpit to relay Cooper's instructions.[15]

Releasing passengers in exchange for demands

Following Cooper's demands, the jet was put into a holding pattern over Puget Sound, while Cooper's demands for $200,000 and four parachutes were met. In assembling the cash demands, F.B.I. agents followed Cooper's instruction for unmarked bills, but they decided to give bills printed mostly in 1969, that mostly had serial numbers beginning with the letter L, issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.[18] The agents also ran all of the 10,000 $20 bills quickly through a Recordak device to create a microfilm photograph of each bill and thus record all the serial numbers.[16][19] Authorities initially intended to obtain military-issue parachutes from McChord Air Force Base, but Cooper said he wanted civilian parachutes, which had manually operated ripcords. Seattle police were able to find Cooper's preferred parachutes at a local skydiving school.[18] Meanwhile, Cooper sat in the airplane, drinking a cocktail of bourbon whiskey and lemon-lime soda, which he would offer to pay for. Tina Mucklow, a flight attendant who spent the most time with the hijacker, remarked Cooper "seemed rather nice," and thoughtful enough to request the crew be brought meals after the jet landed in Seattle.[18] However, F.B.I. investigators for the Cooper case claim the hijacker was "obscene," and used "filthy language."[18] At 17:24 (5:24 pm), airport traffic control radioed Scott and told him that Cooper's demands had been met. Cooper then gave Captain Scott permission to land at the flight's intended destination, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) near Seattle, Washington. The plane landed at the airport at 17:39 (5:39 pm).[20]

The civilians left the plane because Cooper's actions were kept secret from the passengers as to not stir panic. Among the released passengers was flight attendant Schaffner. Pilot Scott, flight attendant Mucklow, First Officer William Rataczak and flight engineer H.E. Anderson were not permitted to leave the aircraft.[20] Cooper then instructed Scott to taxi the plane to a remote section of the tarmac and also dim the lights in the cabin to deter police snipers. He instructed air traffic control to send one person to deliver the $200,000 and four parachutes, unaccompanied.[20] The person chosen, a Northwest Orient employee, drove to the plane and delivered the cash and parachutes to flight attendant Mucklow, via the aft stairs.

The F.B.I. was puzzled regarding Cooper's plans, and his request of four parachutes. The agents wondered if Cooper had an accomplice on board, or if the parachutes were intended for the four crew members who were still on the plane.[18] Up to this point in history, nobody had ever attempted to jump with a parachute from a hijacked commercial aircraft. While the plane was being refueled, an FAA official, who wanted to explain to the hijacker the legal consequences of air piracy, walked to the door of the plane and asked Cooper's permission to come aboard the plane. Cooper promptly denied the official's request.[21] A vapor lock in the fuel tanker truck's engines slowed down the refueling process. Cooper became suspicious when the refueling had still not been completed after 15 minutes. He made threats to blow up the plane, upon which the fuel crew promptly tried to speed up the job until completion.[20]

Back in the skies

After refueling, careful examination of the ransom and parachutes, and negotiations regarding the flight pattern and the position of the aft stairs upon take-off, Cooper ordered the flight crew to take the hijacked jet back into the air at around 19:40 (7:40 pm). The crew was ordered to fly to Mexico City, at a relatively low speed of 170 knots (310 km/h; 200 mph), an altitude at or under 10,000 feet (3,000 m) (normal cruising altitude is between 25,000 and 37,000 feet (7,600 and 11,000 m)), with the landing gear down and 15 degrees of flap.[22] However, First Officer Rataczak told him that the jet could only fly 1,000 miles (1,600 km) under the altitude and airspeed conditions Cooper ordered. Cooper and the crew discussed other possible locations, before deciding on flying to Reno, Nevada, where they would again refuel.[20] They also agreed to fly on Victor 23 as depicted on the Jeppesen air navigational charts, a low-altitude Federal airway that passed west of the Cascade Range. Cooper then ordered Scott to leave the cabin unpressurized. An unpressurized cabin at 10,000 feet would curtail the risk of a sudden rush of air exiting the plane (and ease the opening of the pressure door) if he were to attempt to exit the aircraft for a subsequent parachute landing.[20]

Immediately upon takeoff, Cooper asked Mucklow, who had previously been sitting with him, to go back to the cockpit and stay there.[23] Before she went behind the curtain that separates the coach and first-class seats, she watched him tie something to his waist with what she thought was rope. Moments later in the cockpit, the crew noticed a light flash indicating that Cooper attempted to operate the door. Over the intercom, Scott asked Cooper if there was anything they could do for him, but the hijacker replied curtly, "No!"[23]

The crew started to notice a change of air pressure in the cabin (an "ear popping experience"). Cooper had lowered the aft stairs and jumped out of the plane never to be seen again.[24] That was the last time he was known to be alive. The F.B.I. believed his descent was at 20:13 (8:13 pm) over the southwestern portion of the state of Washington, because the aft stairway "bumped" at this time, most likely because of the weight of Cooper being released from the aft stairs. At the time Cooper jumped, the plane was flying through a heavy rainstorm, with no light source coming from the ground because of cloud coverage.[7] Because of the poor visibility, his descent went unnoticed by the United States Air Force F-106 jet fighters tracking the airliner.[25] He initially was believed to have landed southeast of the unincorporated area of Ariel, Washington, near Lake Merwin, 30 miles (48 km) north of Portland, Oregon ().[26] Later theories based on a variety of sources—including testimony on weather conditions from Continental Airlines pilot Tom Bohan, who had been flying 4,000 feet (1,200 m) above and 4 minutes behind Flight 305—placed Cooper's landing zone as much as 20 miles (32 km) farther east, but its precise location remains unknown.[27]

Nearly 2½ hours after take-off from Seattle-Tacoma, at approximately 22:15,[23] with the aft stairs dragging on the runway, the Boeing 727 landed safely in Reno. The airport and runway were surrounded by F.B.I. agents and local police. After communicating with Captain Scott, it was determined Cooper was gone, and F.B.I. agents boarded the plane to search for any evidence left behind. They recovered a number of fingerprints (which may or may not have belonged to Cooper), a tie and a mother of pearl tie clip, and two of the four parachutes.[28] Cooper was nowhere to be found, nor was his briefcase, the money, the moneybag, or the two remaining parachutes. The individuals with whom Cooper had interacted on board the plane and while he was on the ground were interrogated to compile a composite sketch; those interviewed all gave nearly identical descriptions of him, leading the F.B.I. to create the sketch that has been used on wanted posters ever since, where Dan Cooper is described as being of Latin appearance.[29] As of 2009[update], the F.B.I. maintains that the sketch is an accurate likeness of Cooper because so many individuals, interviewed simultaneously in separate locations, gave nearly identical descriptions.[7]

Vanished without a trace

Despite aerial and ground searches of the projected 28-square-mile (73 km2) landing zone in late 1971 and spring 1972, no trace of Cooper or his parachute was found. An exact landing point was difficult to determine, as the plane's 300 feet (91 m)-per-second speed in winds varying by location and altitude would make even small differences in timing move the projected landing point considerably. This led the F.B.I. to determine that Cooper could not have known exactly where he would land, and therefore must not have had an accomplice waiting to assist him upon landing.[7] Initial search efforts combined small groups of F.B.I. agents with local Clark County and Cowlitz County sheriff's deputies, who probed on foot and by helicopter. Others ran patrol boats along Lake Merwin and Yale Lake.[30] Because months passed with no significant leads coming from anywhere else, the arrival of the spring thaw provided incentive for a thorough ground search, conducted by the F.B.I. and no fewer than 200 U.S. Army troops from nearby Fort Lewis. Teams of agents and soldiers searched the area virtually yard by yard for eighteen straight days in March and for another eighteen straight days in April 1972. After a combined six weeks of searching the projected drop zone, one of the most intense manhunts in the history of the northwestern U.S. revealed no evidence related to the hijacking.[31] As a result, it remains widely disputed whether Cooper actually landed outside the initial estimated drop zone, as well as whether he survived the jump and subsequently escaped on foot. Shortly after the hijacking, the F.B.I. questioned and then released a Portland man by the name of D. B. Cooper, who was never considered a significant suspect. Because of a miscommunication with the media, however, the initials "D. B." became firmly associated with the hijacker and this is how he is now known.[24]

Meanwhile, the F.B.I. also stepped up efforts to track the 10,000 ransomed $20 bills by notifying banks, savings and loan companies, and other businesses of the notes’ serial numbers. Law enforcement agencies around the globe, including Scotland Yard, also received information on Cooper and the serial numbers. In the months following the hijacking, Northwest Airlines offered a reward of 15 percent of the recovered money up to a maximum of $25,000, but the airline eventually canceled the offer as no new substantial evidence seemed to arise.[32] In November 1973, The Oregon Journal, based in Portland, began publishing the first public listings of the serial numbers with permission from the F.B.I. and offered $1,000 to the first person who could claim to have found a single one of the $20 bills.[32] Later, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer offered a $5,000 reward for one of the bills.[33] Despite reported interest from around the country and several alleged near-matches, the newspapers never received a claim of an exact serial number match. In the decade before the Cooper hijacking, local law enforcement and the F.B.I. had solved at least two major crimes—a bank robbery and an extortion—in the Pacific Northwest by tracing money serial numbers. But both cases, which took only weeks for authorities to solve, involved instances of a perpetrator spending the traceable money only days after the crime and in the same general region of the crime,[34] circumstances that in all likelihood did not apply in the Cooper case.

In late 1978, a hunter walking just a few flying minutes north of Cooper's projected drop zone found a placard with instructions on how to lower the aft stairs of a 727. The placard was from the rear stairway of the plane from which Cooper jumped.[35]

On February 10, 1980, Brian Ingram, then eight years old, was with his family on a picnic when he found $5,880 in decaying bills (a total of 294 $20 bills), still bundled in rubber bands, approximately 40 feet (12 m) from the waterline and just 2 inches (5 cm) below the surface, on the banks of the Columbia River 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Vancouver, Washington.[36] After comparing the serial numbers with those from the ransom given to Cooper almost nine years earlier, it was proven that the money found by Ingram was part of the ransom given to Cooper.[35] Upon the discovery, then-F.B.I. lead investigator Ralph Himmelsbach declared that the money "must have been deposited within a couple of years after the hijacking" because "rubber bands deteriorate rapidly and could not have held the bundles together for very long."[37] However, several area scientists recruited by the F.B.I. for assistance with the case noted their belief that the money arrived at the beach as a result of a 1974 Army Corps of Engineers dredging operation. Furthermore, some scientists estimated that the money’s arrival must have occurred even later. Geologist Leonard Palmer of Portland State University, for example, reportedly concluded that the 1974 dredging operation did not place the money on the Columbia's riverbank because Ingram had found the bills above clay deposits put on shore by the dredge.[38] The F.B.I. generally agree now that the money had to have arrived at the location on the riverbank no earlier than 1974. Some investigators and hydrologists have theorized that the bundled bills washed freely into the Columbia River from one of its many connecting tributaries, such as the Washougal River, which originate or run near Cooper's suspected landing zone.

Ingram's discovery of the $5,880 reinforced the F.B.I.'s belief that Cooper probably did not survive the jump, in large part because of the unlikelihood that such a criminal would be willing to leave behind any of the loot for which he had risked his life. Authorities eventually allowed Ingram to keep a split of about $2,860 of the recovered money, with the amount being a rough estimate because of the badly deteriorated condition of the bills. On June 13, 2008, in accordance with Ingram's wishes, the Heritage Auction Galleries' Americana Memorabilia Grand Format Auction in Dallas, Texas sold fifteen of the bills to various buyers for a total of more than $37,000.[39] As of 2010[update], the rest of the money remains unrecovered. The serial numbers of all 9,998 $20 bills that the hijacker was given were databased and placed in a search engine for public search.[40]

Suspects

The F.B.I. has investigated over a thousand "serious suspects" and ruled out most of them.[4]

The F.B.I. believed that Cooper was familiar with the Seattle area, as he was able to recognise Tacoma from the air while the jet was circling over the Puget Sound. He also remarked to flight attendant Mucklow that McChord Air Force Base was approximately 20 minutes from the Seattle-Tacoma Airport. Although the F.B.I. initially believed that Cooper might have been an active or retired member of the United States Air Force, based on his apparent knowledge of jet aerodynamics and skydiving,[18] it later changed this assessment, deciding that no experienced parachutist would have attempted such a risky jump and the fact that Cooper chose an older parachute from the two which were packed in the craft. The other was a professional sport parachute, the ideal choice.[7]

John List

In 1971, mass-murderer John List was considered a suspect in the Cooper hijacking, which occurred only fifteen days after he had killed his family in Westfield, New Jersey. List's age, facial features, and build were similar to those described for the mysterious skyjacker.[41] F.B.I. agent Ralph Himmelsbach stated that List was a "viable suspect" in the case.[35] Cooper parachuted from the hijacked airliner with $200,000, the same amount List had used up from his mother's bank account in the days before the killing.[42] After his capture and imprisonment in 1989, List strenuously denied being Cooper, and the F.B.I. no longer considered him a suspect.[35] List died in prison custody on March 21, 2008.[43]

Richard McCoy, Jr.

On April 7, 1972, four months after Cooper's hijacking, Richard McCoy, Jr., under the alias "James Johnson," boarded United Airlines Flight 855 during a stopover in Denver, Colorado, and gave the flight steward an envelope labeled "Hijack Instructions," in which he demanded four parachutes and $500,000.[35] He also instructed the pilot to land at San Francisco International Airport and order a refueling truck for the plane.[44] The airplane was a Boeing 727 with aft stairs, which McCoy used in his escape. He was carrying a paper weight grenade and an empty pistol. He left his handwritten message on the plane, along with his fingerprints on a magazine he had been reading, which the F.B.I. later used to establish positive identification.

Police began investigating McCoy following a tip from Utah Highway Patrolman Robert Van Ieperen, who was a friend of McCoy's.[45] Apparently, after the Cooper hijacking, McCoy had made a reference that Cooper should have asked for $500,000, instead of $200,000. He had a record as a Vietnam veteran and was a former helicopter pilot.[46]

On April 9, following the fingerprint and handwriting match, McCoy was arrested for the United 855 hijacking.[44][46] McCoy claimed innocence, but was convicted and received a 45-year sentence. Once incarcerated, using his access to the prison's dental office, McCoy fashioned a fake handgun out of dental paste. He and a crew of convicts escaped in August 1974 by stealing a garbage truck and crashing it through the prison's main gate. It took three months before the F.B.I. located McCoy in Virginia. McCoy shot at the F.B.I. agents, and agent Nicholas O'Hara fired back with a shotgun, killing him.[44]

In 1991, Bernie Rhodes and former F.B.I. agent Russell Calame coauthored D.B. Cooper: The Real McCoy, in which they claimed that Cooper and McCoy were really the same person, citing similar methods of hijacking and a tie and mother-of-pearl tie clip, left on the plane by Cooper. The authors said that McCoy "never admitted nor denied he was Cooper."[47] And when McCoy was directly asked whether he was Cooper he replied, "I don't want to talk to you about it."[44] The agent who killed McCoy is quoted as supposedly saying, "When I shot Richard McCoy, I shot D. B. Cooper at the same time."[44] The widow of Richard McCoy, Karen Burns McCoy, reached a $120,000 legal settlement with the book's co-authors and its publisher,[44] after claiming they misrepresented her involvement in the hijacking and later events from interviews done with her attorney in the 1970s.[48]

F.B.I. Special Agent Larry Carr does not believe McCoy was Cooper, saying McCoy didn't match the description and that he was at home the day after the hijacking having Thanksgiving dinner with his family in Utah.[49]

Duane Weber

In July 2000, U.S. News & World Report ran an article about a widow in Pace, Florida, named Jo Weber and her claim that her late husband, Duane L. Weber (born 1924 in Ohio), had told her "I'm Dan Cooper" before his death on March 28, 1995.[4] She became suspicious and began checking into his background. Weber had served in the Army during World War II and had later served time in a prison near the Portland airport. Weber recalled that her husband had once had a nightmare where he talked in his sleep about jumping from a plane and said something about leaving his fingerprints on the aft stairs.[50] Jo recalled that shortly before Duane's death, he had revealed to her that an old knee injury of his had been incurred by "jumping out of a plane."[4]

Weber also recounts a 1979 vacation the couple took to Seattle, "a sentimental journey," Duane told Jo, with a visit to the Columbia River.[4] She remembers how Duane walked down to the banks of the Columbia by himself just four months before the portion of Cooper's cash was found in the same area. Weber related that she had checked out a book on the Cooper case from the local library and saw notations in it that matched her husband's handwriting. She began corresponding with Himmelsbach, the former chief investigator of the case, who subsequently agreed that much of the circumstantial evidence surrounding Weber fit the hijacker's profile. However, the F.B.I. stopped investigating Weber in July 1998 because of a lack of evidence.[4]

The F.B.I. compared Weber's prints with those processed from the hijacked plane and found no matches.[50] In October 2007, the F.B.I. stated that a partial DNA sample taken from the tie that Cooper had left on the plane did not belong to Weber.[7]

Kenneth Christiansen

The October 29, 2007 issue of New York magazine stated that Kenneth P. Christiansen had been identified as a suspect by Sherlock Investigations. The article noted that Christiansen was a former U.S. Army paratrooper, a former Northwest Airlines employee, had settled in Washington state near the site of the hijacking, was familiar with the local terrain, had purchased property with cash a year after the hijacking, drank bourbon and smoked (as did Cooper during the flight) and resembled the eyewitness sketches of Cooper.[11] Nevertheless, the F.B.I. ruled out Christiansen because his complexion, height, weight and eye color did not match the descriptions given by the passengers or the crew of Flight 305.[51]

However, a new book released in April 2010 by Adventure Books of Seattle, titled Into The Blast - The True Story of D.B. Cooper offered new witness testimony and photographic evidence that claim Christiansen was the hijacker. One picture in the book shows Christiansen in December 1971, about three weeks after the hijacking, walking in through the front door of his apartment, unit J-3 at the Rainier View Apartments in Sumner, Washington. He is carrying a briefcase and a paper bag in the picture - the same items carried on board Flight 305 by the hijacker, and is dressed similarly to the hijacker. This picture was discovered after Christiansen's death in a photo album, hidden behind another picture. It was believed at first to be a self-portrait, but that theory was later discarded. The authors now theorize that the picture was probably taken by an accomplice to serve as a personal mememto for Christiansen, which he hid away later.

Two of the key witnesses interviewed for the book were brother and sister. The brother was friends with Christiansen for nearly forty years. The sister (known in the book as 'Dawn J' from Fox Island, Washington) admitted receiving a $5,000 cash loan from Christiansen five months after the hijacking to put a down payment on a house in Bonney Lake, WA. Never questioned previously about Christiansen or the hijacking, she said she had suspected he was the hijacker for many years. When the authors asked her why she never confronted him about it, she replied, “It would have been bad manners. He worked there and he was a nice guy. No one was going to ask about that to his face. Besides, he didn’t look like a criminal." She also said Christiansen owned a toupée, but that he never wore it at his airline job, only socially, and that she never saw him wear it again after the hijacking. She also testified receiving several expensive gifts from Christiansen purchased when he was on layovers in Asia for the airline. The brother (known in the book as 'Mike Watson' from Sequim, Washington) testified that he was never friends with Christiansen and was gone for ten to eleven months at a time working on a tugboat for a company in Seattle.

Testimony from an executive at the tug company disputed this claim, saying the usual length of time employees were out was no more than two weeks. Watson's claim that he was never friends with Christiansen is highly suspect. It is known that Christiansen was best man at Watson's wedding in 1968, that Christiansen was a regular visitor to Watson's home in Bonney Lake, and that they worked together for several years, including a close-knit relationship on Shemya Island in the Aleutians while both of them worked maintenance there for Northwest Airlines. Rick Cochran, the communications officer on Shemya while Christiansen was stationed there, testified that he saw the famous 'Dan Cooper' comic book by Albert Weinberg in the Day Room there, which shows a man on the cover parachuting out of an airplane. Northwest employees often stopped in at the Day Room to hunt for new reading material, since there was no radio or television on the island. This comic has been linked by the F.B.I. as a possible clue to the hijacker's identity.

Another witness, Watson's ex-wife in Twisp, Washington (known as 'Katy Watson' in the book) presented a series of logbooks from the tug on which Watson worked from approximately 1965 to 1973. The logbook for 1971 was missing. She testified that Watson had broken into her home shortly after Christiansen's death and stolen it, along with some personal papers. She also pointed out discrepancies in the remaining logs, claiming that her ex-husband had occasionally been collecting two paychecks from the tug company for a substantial period of time. The authors of the book believe that if Watson stole the 1971 logbook, it was because the logbook could prove he was not at work the week of the hijacking, not to hide his tracks about the discrepencies. If that were the case, they say, Watson would have taken all of the logs, which were stored together in the same small box. The ex-wife also testified that a few days prior to the hijacking, Watson left their home in Bonney Lake with a recently-purchased Airstream trailer and a station wagon and did not return until two days after the crime. When he did return, he had an unexplained foot and back injury, for which he later sought treatment at one of the Puget Sound area Swedish Medical Centers. The trailer and station wagon were either sold by Watson soon afterward, or allowed to go back to the bank. The authors believe that 'Mike Watson' was the person who helped plan the hijacking, transported Cooper to Portland, and then picked him up on the ground afterward. During separate interviews for the book, both 'Mike Watson' and his ex-wife 'Katy' each tried to point a finger at the other as possibly being involved. The authors think both of them may have been involved.

Officially, the F.B.I. does not believe the hijacker was Christiansen, mostly based on the physical description given by witnesses. The authors point out that these witnesses originally gave different estimates of the hijacker's height and that they could simply be wrong. A copy of Christiansen's 1993 drivers' license lists his eye color as hazel, but in the picture they appear brown. Witnesses also said the hijacker had an olive complexion. Personal letters home to Minnesota by Christiansen state he was on the beach in Japan frequently on layovers, and was well-tanned.

After Christiansen's death in 1994, his family discovered valuable gold coin and stamp collections at his house in Bonney Lake, and a folder of news clippings about Northwest Airlines. The clippings begin in the 1950s when he worked on Shemya Island, and stop just before the date of the hijacking. There were no clippings about the hijacking, even though Christiansen continued to work part-time for the airline for many years after 1971.

William Gossett

On August 4, 2008, Canadian Press reported that a Spokane, Washington, lawyer believes that the ransom money is stored in a Vancouver, British Columbia, safe deposit box under the name of William Gossett, a college instructor from Ogden, Utah, who died in 2003. Lawyer Galen Cook says that Gossett matches the sketches circulated by the F.B.I.. Also, Gossett is alleged to have bragged to his sons about the hijacking and shown them a key to the safe deposit box.[52] Gossett is also said to have confessed to two people, including a judge and a lawyer, and his own son also believed his father to be the hijacker.[53] By fleeing from the country, Cooper would be out of law enforcement boundaries. (The value of this is unclear given Canada's extradition treaty with the United States, though the current treaty came into effect five years after the hijacking.)

Aftermath

Effect on the airline industry

The hijacking caused major changes in commercial flight safety, mainly in the form of metal detectors added to the airports by the airline companies, several related flight safety rules set in place by the FAA, and modifications made to the Boeing 727 aircraft. Following three similar but less successful hijackings in 1972, the Federal Aviation Administration required that all Boeing 727 aircraft be fitted with a device known as the "Cooper vane", a mechanical aerodynamic wedge that prevents the airstair or rear stairway of an aircraft from being lowered in flight.[17]

Renewed F.B.I. interest and new evidence

On November 1, 2007, the F.B.I. released detailed information concerning some of the evidence in their possession, which they had not revealed to the public before.[54] The F.B.I. displayed Cooper's 1971 plane ticket from Portland to Seattle, which cost $18.52. It also revealed that he requested four parachutes—two main back chutes and two reserve chest chutes. Authorities inadvertently supplied Cooper with a "dummy" reserve chute—an unusable parachute that is sewn shut for classroom demonstration. The dummy chute was not left behind on the plane, and some theorize Cooper did not realize it was not functional.[54] This piece of information had been revealed in a 1979 episode of TV documentary series In Search of.... The other reserve parachute, which was a functional parachute, was popped open and the shrouds were cut and supposedly used to secure the money bag.

On December 31, 2007, the F.B.I. issued a press release online containing never before seen photos and fact sheets in an attempt to trigger memories or useful information regarding Cooper's identity. In the fact sheets, the F.B.I. withdrew its previous theory that Cooper was either an experienced skydiver or paratrooper.[55] While it was initially believed that Cooper must have had training to have performed such a feat, later analysis of the chain of events led the F.B.I. to reevaluate this claim. Investigators said that no experienced paratrooper or skydiver would attempt a jump during a rainstorm with no light source.[55] Investigators also believe that, even if Cooper was in a hurry to escape, an experienced jumper or paratrooper would have stopped to inspect his chutes.[7]

On March 24, 2008, the F.B.I. announced that it was in possession of a parachute recovered from a field in northern Clark County, Washington, near the town of Amboy. A property owner was in the process of making a private road with a bulldozer when the blade caught some cloth, and his children pulled the cloth until the canopy lines appeared. Earl Cossey, the man who provided the four parachutes that were given to Cooper by the F.B.I., examined the newly found chute and on April 1, 2008 said that "absolutely, for sure" it could not have been one of the four that he supplied in 1971. The Cooper parachutes were made of nylon, unlike the new chute that was recovered which is made of silk and most likely made around 1945.[56] The F.B.I. later made a press release confirming Cossey's findings. Investigators reached their official conclusion after consulting with Cossey and other parachute experts. "From the best we could learn from the people we spoke to, it just didn't look like it was the right kind of parachute in any way," said F.B.I. spokeswoman Robbie Burroughs.[57] Further digging at the site in southwestern Washington turned up no indication that it could have been Cooper's.[57]

F.B.I. Special Agent Larry Carr has theorized that Cooper took his alias from Dan Cooper, a French-Canadian comic book hero who is a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force and is depicted parachuting on the cover of one issue. This is referenced in the new book on the Cooper case by Adventure Books of Seattle, who note that Kenny Christiansen worked for three and a half years on Shemya Island, Alaska and saw copies of the comic in the Day Room. This is supported by an interview in the book conducted with a communications officer who worked on Shemya at the same time as Christiansen.[58]

Cultural phenomenon

Cooper's daring and unprecedented acts inspired a cult following, expressed through song, film and literature. Cities in the Pacific Northwest sold tourist souvenirs and held celebrations in his memory. He is remembered in Ariel, Washington with a 'Cooper Day' event held annually on the weekend after Thanksgiving weekend, and elsewhere with Cooper-themed promotions held by restaurants and bowling alleys.[59]

In the television series Prison Break Michael Scofield believes Charles Westmoreland to be D.B. Cooper.

See also

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously

- Cold case

- Samuel Byck

- Philippine Airlines Flight 812

Footnotes

- ↑ Adjusted for inflation, $200,000 in 1971 has the buying power of over $1,000,000 in 2008. "Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator". United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ "F.B.I. makes new bid to find 1971 skyjacker". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. 2008-01-01. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2008/01/01/national/a100412S30.DTL. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Himmelsbach, Ralph P.; Thomas K. Worcester (1986). Norjak: The Investigation of D. B. Cooper. West Linn, Oregon: Norjak Project. p. 135. ISBN 0-9617415-0-3.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Pasternak, Douglas (2000-07-24). "Skyjacker at large". U.S. News & World Report. http://www.usnews.com/usnews/doubleissue/mysteries/cooper.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ "Did children find D.B. Cooper’s parachute?". MSNBC. 2008-03-25. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23801264/. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ "Cash linked to 'D.B. Cooper' up for auction". MSNBC. 2008-03-31. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23889269. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 "D.B. Cooper: Help Us Solve the Enduring Mystery". F.B.I.. 2007-12-31. http://www.F.B.I..gov/page2/dec07/dbcooper123107.html. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ "Interview with lead F.B.I. Investigator Larry Carr". Steven Rinehart. 2008-02-02. http://www.stevenrinehart.com/uploads/LarryCarrInterview.mp3. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ Olson, James S. (1999). Historical Dictionary of the 1970s. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-313-30543-9.

- ↑ Tizon, Tomas A. (2005-09-04). "D.B. Cooper -- the search for skyjacker missing since 1971". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/09/04/BAGU1EG7K71.DTL. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gray, Geoffrey (2007-10-22). "Unmasking D.B. Cooper". New York. http://nymag.com/news/features/39593/. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ↑ Bragg, Lynn E. (2005). Myths and Mysteries of Washington. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot. p. 2. ISBN 0-7627-3427-2.

- ↑ Steven, Richard (1996-11-24). "When D.B. Cooper Dropped From Sky: Where did the daring, mysterious skyjacker go? Twenty-five years later, the search is still on for even a trace.". The Philadelphia Inquirer: p. A20.

- ↑ Burkeman, Oliver (2007-12-01). "Heads in the clouds". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/weekend/story/0,,2218788,00.html. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: The Crime". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/2.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bragg, p. 3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gilmore, Susan (2001-11-22). "D.B. Cooper puzzle: The legend turns 30.". The Seattle Times. http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com/cgi-bin/texis.cgi/web/vortex/display?slug=cooper22m&date=20011122. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: Meeting the Demands". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/4.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Himmelsbach and Worcester, p. 25

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: 'Everything Is Ready'". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/5.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Rothenberg, David; Marta Ulvaeus (1999). The New Earth Reader: The Best of Terra Nova. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-262-18195-9.

- ↑ Rothenberg and Ulvaeus, p. 5.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: The Jump". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/6.html. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Bragg, p. 4.

- ↑ Taylor, Michael (1996-11-24). "D.B. Cooper legend still up in air 25 years after leap, hijackers prompts strong feelings". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Skolnik, Sam (2001-11-22). "30 years ago, D.B. Cooper's night leap began a legend". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/47793_vanished22.shtml. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ Himmelsbach and Worcester, p. 111-113

- ↑ Cowan, James (2008-01-03). "F.B.I. reheats cold case". National Post. http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=211616. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ F.B.I. FOIA file part 1, from F.B.I. FOIA catalogue on the Dan Cooper case, also see the actual F.B.I. poster.

- ↑ Himmelsbach and Worcester, p. 67-68.

- ↑ Himmelsbach and Worcester, p. 87-89.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Crick, Rolla J. (1973-11-22) (PDF). 1,000 Offered For First $20 Bill. The Oregon Journal. p. 25. http://foia.F.B.I..gov/cooper_d_b/cooper_d_b_part07.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Himmelsbach and Worcester, p. 95.

- ↑ Crick, Rolla J. (1973-02-23) (PDF). Winner of D.B. Cooper $20 Bill Hunt Gets $1,000. The Oregon Journal. p. 7. http://foia.F.B.I..gov/cooper_d_b/cooper_d_b_part06.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Coreno, Catherine (2007-10-22). "D.B. Cooper: A Timeline". New York. http://nymag.com/news/features/39617/. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ↑ "D.B. Cooper's loot to be auctioned off". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. 2006-02-13. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2002802076_dbcooper13m.html. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ "DB Cooper" (PDF). Associated Press. 1980-02-14. p. 15. http://foia.F.B.I..gov/cooper_d_b/cooper_d_b_part07.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "DB Cooper" (PDF). Associated Press. 1980-02-14. p. 19. http://foia.F.B.I..gov/cooper_d_b/cooper_d_b_part07.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "D.B. Cooper Skyjacking Cash Sold in Dallas Auction". Associated Press. 2009-06-13. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,366923,00.html. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Benford, James P. Johnson, Timothy B; James P. Johnson (2000). Righteous Carnage: The List Murders in Westfield. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse. pp. 76–77. ISBN 0-595-00720-1.

- ↑ "Suspect in Family-Slaying May Be Famed D.B. Cooper". Los Angeles Times: p. A1. 1989-06-30.

- ↑ Stout, David (2008-03-25). "John E. List, 82, Killer of 5 Family Members, Dies". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/25/nyregion/25list1.html?em&ex=1206590400&en=54ef92d43724f8e2&ei=5087%0A. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: The Copycats". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/9.html. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ "Skydiver Held as Hijacker; $500,000 Is Still Missing". Associated Press. 1972-04-10.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Famous Cases: Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr. - Aircraft Hijacking". F.B.I.. http://www.F.B.I..gov/libref/historic/famcases/mccoy/mccoy.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Schindler, Harold (1996-11-24). "25 Years Later, 'D.B' Remains Tied to Utah; Skyjacker Took Story To His Grave". Salt Lake Tribune.

- ↑ "Widow of Man Linked in Book to Skyjacker D.B. Cooper Sues Authors, Provo Attorney". Associated Press. 1992-01-18. p. B5.

- ↑ Hamilton, Don (2004-10-23). "F.B.I. makes new plea in D.B. Cooper case". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Krajicek, David. "The D.B. Cooper Story: "I'm Dan Cooper. So Am I."". Crime Library. http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/10.html. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ↑ "F.B.I. rejects latest D.B. Cooper suspect". Associated Press. 2007-10-26. http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/337121_dbcooper27.html. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ↑ "U.S. lawyer believes notorious fugitive D.B. Cooper hid ransom money in Vcr bank". Canadian Press. 2008-08-03.

- ↑ "Investigator Claims Depoe Bay Man Was Infamous 'D.B. Cooper'". Depoe Bay Beacon. 2008-05-28.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Ingalls, Chris (2007-11-01). "Investigators: F.B.I. unveils new evidence in D.B. Cooper case". King 5. http://www.king5.com/localnews/stories/NW_110107INK_cooper_chute_KS.1cbb87e02.html. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Tedford, Deborah (2008-01-02). "F.B.I. Seeks Help in Solving Skyjacking Mystery". National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17787290. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ↑ "Parachute 'absolutely' not Cooper's". MSNBC. 2008-04-01. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23903655/. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Johnson, Gene (2008-04-02). "F.B.I.: Parachute Isn't Hijacker Cooper's". Associated Press. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2008-04-01-1583187205_x.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ "In Search of D.B. Cooper: New Developments in the Unsolved Case". F.B.I. Headline Archives. 2009-03-17. http://www.F.B.I..gov/page2/march09/dbcooper031709.html. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ Slatta, Richard W. (2001). The Mythical West: An Encyclopedia of Legend, Lore and Popular Culture. Over the years there have been a few small bars in various United States cities named D.B. Cooper's.

Further reading

- Himmelsbach, Ralph P.; Thomas K. Worcester (1986). Norjak: The Investigation of D. B. Cooper. West Linn, Oregon: Norjak Project. ISBN 0-9617415-0-3.

- Tosaw, Richard T. (1984). D.B. Cooper: Dead or Alive?. Tosaw Publishing. ISBN 0960901612. The book includes a full list of serial numbers from the $20 notes that were given to Cooper.

- Porteous, Skipp; Robert M. Blevins (2010). Into the Blast - The True Story of D.B. Cooper. Seattle, Washington: Adventure Books of Seattle. ISBN 978-0-9823271-2-8.

External links

- F.B.I. FOIA Reading Room Files of the "Norjak" D.B. Cooper Case

- D.B. Cooper Memorial At Find A Grave

- Check-Six.com - Codename:Norjak - The Skyjacking of Northwest Orient Flight 305

- Radio interviews about D. B. Cooper's identity with major authors

- Nov. 27, 1971, account of the hijacking in the Minneapolis Tribune

- Radio interview with F.B.I. lead investigator Larry Carr

- Video tour of D.B. Cooper evidence with F.B.I. lead investigator Larry Carr

- PCGS Currency Notifies F.B.I. of “D. B. Cooper” Serial Numbers

- Check-Six.com - D B Cooper's Loot Serial Number Search Engine

- Fifteen D.B. Cooper $20 Notes make $37K at Auction

- Northwest 305 Hijacking Research Site

- Cooper '71 - D.B. Cooper Archives

- "D.B. Cooper". The Columbian. 1989. Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. http://web.archive.org/web/20070617035421/http://www.columbian.com/history/profiles/cooper.cfm. Retrieved 2007-06-13.